Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences

Volume 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

DYNAMIC CAPABILITIES AS GENERATIVE MECHANISMS: INSIGHTS FROM

BEÉLE’S BORONDO AND THE AFROBEAT MUSIC SECTOR

LAS CAPACIDADES DINÁMICAS COMO MECANISMOS GENERATIVOS:

PERSPECTIVAS DESDE BORONDO DE BEÉLE Y EL SECTOR DE LA MÚSICA

AFROBEAT

Javier Alfonso Mendoza Betin

Colombia

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

1925 Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences | Vol. 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

Dynamic capabilities as generative mechanisms: insights from Beéle’s Borondo

and the Afrobeat music sector

Las capacidades dinámicas como mecanismos generativos: perspectivas desde

Borondo de Beéle y el sector de la música Afrobeat

Javier Alfonso Mendoza Betin

j.mendozabetin@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8355-8581

Universidad Internacional Iberoamericana - UNINI México

Colombia

ABSTRACT

Over the past three decades, Dynamic Capabilities (DCs) have emerged as a cornerstone of

strategic management, explaining how organizations adapt, renew, and transform in turbulent

environments. This study extends DC theory into the creative industries, analyzing their

ontological nature in the Afrobeat music sector through the case of Colombian artist Beéle and

his 2025 album Borondo. Using a sequential mixed-methods approach (SEM and in-depth

interviews) with DJs and producers in Cartagena (Colombia), the research examines absorptive,

adaptive, learning, innovative, and resilience capacities. Results confirm that DCs operate as

higher-order generative mechanisms embedded in both artistic and organizational identity. The

study contributes to the theoretical debate by emphasizing the ontological perspective and

offers practical implications for sustaining artistic careers in dynamic environments, while

recognizing contextual limitations.

Keywords: dynamic capabilities; ontological perspective; creative industries; afrobeat;

sustainability

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

1926 Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences | Vol. 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

RESUMEN

En las últimas tres décadas, las Capacidades Dinámicas (DCs) se han consolidado como un

pilar de la gestión estratégica, al explicar cómo las organizaciones se adaptan, renuevan y

transforman en entornos turbulentos. Este estudio amplía la teoría de las DCs hacia las

industrias creativas, analizando su naturaleza ontológica en el sector de la música Afrobeat a

través del caso del artista colombiano Beéle y su álbum Borondo (2025). Mediante un enfoque

mixto secuencial (modelamiento de ecuaciones estructurales e entrevistas en profundidad) con

DJs y productores en Cartagena (Colombia), la investigación examina las capacidades de

absorción, adaptación, aprendizaje, innovación y resiliencia. Los resultados confirman que las

DCs operan como mecanismos generativos de orden superior, incrustados tanto en la identidad

artística como organizacional. El estudio aporta al debate teórico al destacar la perspectiva

ontológica y ofrece implicaciones prácticas para la sostenibilidad de carreras artísticas en

entornos dinámicos, reconociendo sus limitaciones contextuales.

Palabras clave: capacidades dinámicas; perspectiva ontológica; industrias creativas; afrobeat;

sostenibilidad

Received: September 2, 2025 | Accepted: September 19, 2025

INTRODUCTION

In the last three decades, the concept of Dynamic Capabilities (DCs) has become one of

the central pillars of strategic management research. Initially conceived as an extension of the

resource-based view (RBV), DCs have evolved into a robust theoretical and empirical

framework to explain how organizations adapt, renew, and transform themselves in turbulent

environments (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, 1997; Teece, 2007, 2018).

While the RBV emphasized the possession of valuable, rare, and hard-to-imitate resources, the

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

1927 Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences | Vol. 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

DC perspective shifted attention toward the processes and mechanisms by which organizations

reconfigure such resources to achieve sustained competitive advantage. This shift in focus

underscores the increasing importance of understanding organizations not only as repositories

of assets but also as dynamic systems capable of renewal and continuous transformation.

Despite extensive contributions, the literature on DCs has been marked by persistent

debates. A central tension lies in whether DCs should be understood as firm-specific,

idiosyncratic properties (Teece, 2007, 2014) or as industry-common strategic routines whose

effectiveness depends on context (Adner & Helfat, 2003; Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000). Integrative

perspectives (Peteraf, Di Stefano, & Verona, 2013; Mendoza Betin, 2018; Schilke, Hu, & Helfat,

2018) suggest that both positions are not mutually exclusive but coexist within different

contexts. DCs may simultaneously exhibit patterned characteristics that can be generalized

across industries and unique features deeply embedded in organizational identity and

managerial orchestration.

At the core of the DC framework are three microfoundations: sensing opportunities and

threats, seizing them through resource allocation, and transforming the organizational asset

base (Teece, 2007). These processes are complemented by learning mechanisms that

articulate, codify, and routinize experiential knowledge, ensuring the accumulation and

refinement of adaptive capacities over time (Zollo & Winter, 2002). This processual nature

highlights the path-dependent and path-creating dynamics through which organizations not only

react to but also shape their environments (Helfat & Peteraf, 2003; Helfat, 2009). From an

ontological perspective, DCs are conceived as real generative mechanisms that bring about

transformation in routines, structures, and resources (Schreyögg & Kliesch-Eberl, 2007; Winter,

2003), emphasizing their role as higher-order capabilities that transcend operational functions.

Nevertheless, one of the main challenges in advancing this research stream has been

the measurement and validation of DCs as constructs. Scholars have proposed operationalizing

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

1928 Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences | Vol. 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

DCs as higher-order latent variables rather than proxies for innovation or financial performance

(Ambrosini & Bowman, 2009; Barreto, 2010; Wang & Ahmed, 2007). Empirical studies confirm

that DCs impact performance indirectly, primarily through their influence on the renewal of

ordinary capabilities (Protogerou, Caloghirou, & Lioukas, 2012; Wilden et al., 2013). Meta-

analyses also reveal significant but contingent effects, moderated by environmental dynamism,

strategic fit, and industry characteristics (Fainshmidt et al., 2016; Schilke, 2014). These insights

illustrate both the maturity and the complexity of the field.

In contemporary contexts, the scope of DCs has expanded beyond traditional corporate

settings. Digital transformation, business model innovation, and big data analytics have been

incorporated as enablers of sensing and seizing mechanisms (Mikalef et al., 2020; Teece,

2018). Likewise, public sector and non-market domains have recognized the relevance of DCs

in promoting adaptation, innovation, and resilience (Piening, 2013; Zahra, Sapienza, &

Davidsson, 2006). This diversification of contexts has reinforced the need to explore DCs not

only as competence-based and procedural constructs but also as ontological mechanisms

embedded in organizational, cultural, and even artistic practices.

Within this broader landscape, creative industries represent a fertile ground for extending

the theory of dynamic capabilities. The music sector, in particular, is characterized by

accelerated cycles of technological disruption, aesthetic evolution, and shifting consumption

habits. DJs and producers face continuous pressures to absorb external influences, adapt to

digital platforms, learn through experimentation, innovate by hybridizing genres, and remain

resilient in the face of volatility such as cancellations, algorithmic changes, or market saturation.

These dynamics make the sector an ideal laboratory to test the explanatory power of DCs in

environments where artistic identity and organizational logics intersect (Mendoza Betin, 2025).

The Colombian Afrobeat scene, and specifically the trajectory of the artist Beéle and his

2025 album Borondo, provides a paradigmatic case for studying the ontological nature of DCs.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

1929 Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences | Vol. 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

Beéle’s career illustrates how absorptive, adaptive, learning, innovative, and resilience

capacities converge to sustain artistic growth and organizational viability in a highly dynamic

environment. His ability to fuse Afrobeat with local Caribbean influences, leverage digital

platforms, and transform personal and industry challenges into creative outputs exemplifies how

DCs operate beyond procedural routines and reveal themselves as generative mechanisms at

the core of cultural and creative survival.

Against this backdrop, the present study seeks to contribute to the ongoing theoretical

debate by empirically testing the competence-based, procedural, eclectic, and ontological

natures of DCs in the Latin American music sector. By employing a mixed-methods approach,

combining structural equation modeling with in-depth interviews, this research not only

evaluates the explanatory capacity of these perspectives but also advances an integrated

framework that highlights the ontological dimension as essential for understanding the

sustainability of artistic careers in turbulent creative environments.

In doing so, the study positions itself at the intersection of strategic management and

cultural production, aiming to demonstrate that DCs are not merely managerial constructs but

mechanisms embedded in the artistic and organizational essence of creative actors. Thus, the

findings are expected to have both theoretical implications for the refinement of DC theory and

practical implications for the management of artistic careers in dynamic contexts such as the

Afrobeat music industry in Latin America.

Theoretical framework

The nature of dynamic capabilities: a theoretical foundation

Over the last three decades, dynamic capabilities (DCs) have become a cornerstone in

strategic management, evolving from extensions of the resource-based view into a robust

framework for explaining how firms adapt, renew, and transform in turbulent environments.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

1930 Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences | Vol. 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

Seminal contributions emphasize that DCs are firm-specific, hard-to-imitate processes enabling

organizations to sense, seize, and transform in response to environmental shifts (Teece,

Pisano, & Shuen, 1997; Teece, 2007, 2014, 2018), while others highlight that DCs often

resemble identifiable processes whose effectiveness depends on context (Eisenhardt & Martin,

2000). This dual perspective reflects the enduring debate about whether DCs are unique firm-

level properties or more generalizable strategic routines (Peteraf, Di Stefano, & Verona, 2013;

Schilke, Hu, & Helfat, 2018).

Definitions have converged around three interlinked microfoundations: sensing

opportunities and threats, seizing them through resource allocation, and transforming the asset

base through reconfiguration (Pavlou & El Sawy, 2011; Teece, 2007; Verona & Ravasi, 2003).

Distinguishing DCs from ordinary capabilities is fundamental, since the former modify and

reconfigure the latter (Helfat & Winter, 2011). The concept of capability lifecycles further

explains how DCs emerge, evolve, and decline across time (Helfat & Peteraf, 2003).

From an ontological perspective, DCs are understood as real generative mechanisms

that produce transformation in routines, structures, and resources (Schreyögg & Kliesch-Eberl,

2007; Winter, 2003). Their microfoundations include managerial cognition and dynamic

managerial capabilities (Adner & Helfat, 2003; Helfat & Peteraf, 2015). Managerial cognition

provides the interpretive lenses through which firms perceive opportunities and threats, while

dynamic managerial capabilities enable the orchestration of resources in alignment with

environmental change.

Learning processes are central to DCs. Organizations transform experiential knowledge

into deliberate routines through articulation, codification, and routinization (Zollo & Winter,

2002). These learning mechanisms explain how firms accumulate and refine their ability to

innovate and adapt, while path dependence and path creation reveal how historical choices

constrain or enable renewal (Helfat, 2009). This implies that DCs are inherently processual,

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

1931 Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences | Vol. 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

evolving over time through continuous cycles of experimentation and adaptation (Mintzberg,

1994; Teece et al., 1997).

A persistent challenge has been the measurement and validation of DCs as constructs.

Reviews propose operationalizing them as higher-order latent constructs rather than only as

proxies for innovation or performance (Ambrosini & Bowman, 2009; Barreto, 2010; Laaksonen &

Peltoniemi, 2018; Wang & Ahmed, 2007). Empirical studies have clarified their indirect impact

on firm performance, showing that DCs act primarily through the renewal of operational

capabilities (Drnevich & Kriauciunas, 2011; Protogerou, Caloghirou, & Lioukas, 2012; Wilden et

al., 2013). Meta-analyses confirm positive overall effects but highlight contingencies, such as

environmental dynamism and strategic fit (Fainshmidt et al., 2016; Schilke, 2014).

The Eisenhardt–Martin vs. Teece debate has generated constructive synthesis. While

Eisenhardt and Martin (2000) emphasize industry-common routines, Teece (2007, 2018)

underscores firm-specific orchestration. Integrative perspectives recognize that both views

coexist: DCs can be both patterned and idiosyncratic depending on their context (Mendoza

Betin 2018, Peteraf et al., 2013; Schilke et al., 2018).

In contemporary contexts, digital transformation and business model innovation have

expanded the scope of DCs. Business model design is now considered a dynamic capability in

itself (Teece, 2018). Moreover, big data analytics has been identified as an enabling factor for

sensing and seizing opportunities (Mikalef et al., 2020), reinforcing the link between

technological capabilities and strategic renewal.

Finally, DCs are also recognized in public sector and non-market contexts, where

adaptation and renewal are equally critical (Piening, 2013). In such environments, DCs are

embedded in organizational learning, innovation, and resilience, reaffirming their ontological

nature as mechanisms for change (Zahra, Sapienza, & Davidsson, 2006).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

1932 Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences | Vol. 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

In sum, the literature shows that DCs are simultaneously competence-based, processual,

and ontological. They represent higher-order mechanisms that allow organizations to

reconfigure resources, renew strategies, and sustain performance over time (Helfat, 2009;

Schilke, 2014; Teece, 2007). Their importance lies not only in explaining competitive advantage,

but in capturing the very essence of organizational adaptation and survival in dynamic

environments.

Certainty is also found in the work of Mendoza Betin (2019), who thus far has settled the

discussion on the procedural and competence-based nature of dynamic capabilities, adding a

new perspective referred to as eclectic and integrated.

Dynamic capabilities in the music/DJ sector

For at least the past two decades, Dynamic Capabilities (DCs) have been consolidated

as an explanatory framework for understanding how organizations sense, seize, and transform

opportunities in changing environments (Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, 1997; Teece, 2007). In

contrast to the logic of the resource-based view, which emphasizes valuable and hard-to-imitate

resources, DCs focus on change processes that continuously renew ordinary capabilities

(Ambrosini & Bowman, 2009; Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000). This emphasis is particularly relevant

in creative industries such as music, where the speed of aesthetic and technological cycles

demands constant reconfigurations (Mendoza Betin, 2025). For this purpose, the following has

been proposed:

Absorptive capacity. In the music sector, absorption refers to the identification,

assimilation, and exploitation of external influences—genres, grooves, sound textures, mixing

techniques—while preserving an artistic identity. For DJs/producers, this includes musical

curation, digital crate digging, the use of libraries and samples, and the interpretation of cultural

and platform signals (Mendoza Betin, 2025). Effective absorption translates into recombinations

that fuel future innovation.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

1933 Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences | Vol. 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

Adaptive capacity. Adaptation involves adjusting configurations (sets, BPM,

instrumentation, arrangements) in response to environmental signals: recommendation

algorithms, trends (e.g., TikTok), live performance formats (boiler rooms, streaming sessions),

or changes in consumption habits. The literature shows that DCs manifest as recognizable

processes—rapid iteration, stylistic pivoting, portfolio adjustment—whose effectiveness depends

on context and orchestration (Mendoza Betin, 2025).

Learning capacity. Learning transforms experience into deliberate routines: articulation,

codification, and standardization (Zollo & Winter, 2002). In music, this is observed in rehearsal–

feedback–revision cycles (A/B testing of mixes and masters, trials of hooks in previews,

analytical soundchecks). This learning sustains trajectories in which history and previous paths

constrain—but also enable—the development of new competences (Mendoza Betin, 2025).

Innovative capacity. Innovation in music involves reconfiguring genre combinations

(afrobeat/house/reggaetón), hybridizing instruments (acoustic and digital), and designing

business models that capture value (collaborations, catalogs, sync licensing). DC theory

situates innovation as the outcome of sensing supported by data (audience listening, platform

analytics) and seizing through investments and alliances, followed by transforming the portfolio

(Mendoza Betin, 2025).

Resilience capacity. Although resilience is not always explicitly described as a DC in the

classical literature, in creative industries it emerges as the result of capabilities to reconfigure

rapidly in response to shocks (cancellations, demand drops, algorithmic changes). The

resilience of DJs/producers relies on redeploying resources (e.g., shifting from club shows to

livestreams and content creation), sustaining communities, and preserving brand equity during

periods of discontinuity (Mendoza Betin, 2025).

Applied synthesis and local contributions. Empirically, Mendoza Betin (2018, 2019,

2021), and conceptually, Mendoza Betin (2025), have provided clarity by discussing the

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

1934 Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences | Vol. 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

procedural and competence-based nature of DCs, later proposing an eclectic and integrated

perspective, and in 2025, an ontological view that is especially useful in creative sectors where

artistic and managerial logics coexist. Integrating these perspectives with the strategic

framework and with approaches that measure DCs as higher-order constructs (Mendoza Betin,

2025) offers a coherent lens to study absorptive, adaptive, learning, innovative, and resilience

capacities in DJs/producers. In ontological terms, this supports the view that DCs are real

mechanisms generating both artistic and organizational transformation, coinciding with (Teece,

2007; Helfat & Peteraf, 2015).

Given the theoretical perspective outlined above, the following hypotheses are proposed.

Research hypotheses

General hypothesis:

H1: In the Latin American music sector, Dynamic Capabilities of an ontological nature

have a positive and significant effect on the sustainability of artistic careers, particularly in the

Afrobeat genre.

Specific hypotheses:

H1.1: The nature of the dynamic capabilities of absorption, adaptation, learning,

innovation, and resilience is competence-based.

H1.2: The nature of the dynamic capabilities of absorption, adaptation, learning,

innovation, and resilience is procedural.

H1.3: The nature of the dynamic capabilities of absorption, adaptation, learning,

innovation, and resilience is eclectic.

H1.4: The nature of the dynamic capabilities of absorption, adaptation, learning,

innovation, and resilience is ontological.

These hypotheses were tested using the structural equation modeling technique,

adapting the items of the aforementioned Dynamic Capabilities to Beéle’s 2025 album Borondo,

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

1935 Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences | Vol. 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

as it represents an exemplary case of artistic and organizational success. This case is worth

analyzing because it embodies novelty, relevance, and addresses an empirical gap in Latin

America, in line with Mendoza Betin (2025).

METHOD

Approach and type of study

The research employs a non-experimental design and applies a sequential mixed-

methods strategy (Quant → Qual), characterized by an exploratory as well as explanatory–

descriptive orientation. Conducted over a two-month period (July–August 2025), the study

adopts a cross-sectional framework, planned for execution during the third quarter of 2025.

From the quantitative standpoint, the study explores the relationship between the five

dynamic capabilities—absorption, adaptation, learning, innovation, and resilience—and their

different types of natures (competence-based, procedural, eclectic, and ontological). To this

end, four distinct instruments were applied (one for each nature of the dynamic capabilities in

relation to the five capacities mentioned) to a representative sample of DJs and music

producers in Cartagena de Indias. The analysis focuses on the album Borondo and the musical

career of the Colombian artist Beéle (2025), from 2019 to the present. The qualitative phase

subsequently seeks to deepen the understanding of how the actors themselves interpret these

findings, with the aim of building a comprehensive perspective of the phenomenon. The five

dynamic capabilities—absorption, adaptation, learning, innovation, and resilience—were treated

as the dependent variables, while their distinct natures (competence-based, procedural,

eclectic, and ontological) served as the independent variables.

Population and sample

• Target Population: DJs and music producers, most of them owners and managers of

their own businesses.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

1936 Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences | Vol. 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

• Quantitative Sample: A total of 135 professionals were chosen using purposive non-

probability sampling, guided by three main criteria: (a) at least four years of professional

practice, (b) holding a formal leadership role within their organization, and (c) voluntary

willingness to take part in the study.

• Qualitative Sample: Four (4) intentionally selected DJs and music producers.

Data collection techniques and instruments

Quantitative component

Four ad hoc structured questionnaires, each containing 30 Likert-scale items (1–5), were

developed to evaluate six dimensions: dynamic absorptive capacity, dynamic adaptive capacity,

dynamic learning capacity, dynamic innovation capacity, dynamic resilience capacity, and their

corresponding natures—competence-based, procedural, eclectic, and ontological. The design

was grounded in the contributions of Di Stefano, Peteraf & Verona, (2010), Maturana and

Varela (1980, 1987), Mendoza Betin (2019, 2025), Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995), Teece (2018),

and Winter (2003). The construction process unfolded across three sequential phases:

1. Initial design

o Review of the literature and adjustment of previously validated scales.

o Formulation of items consistent with the study’s objectives and hypotheses.

2. Content validity

o Review conducted by three experts (two holding PhDs in Organizational

Behavior and one with a Master’s in Business Administration), in accordance with

the guidelines of Hernández-Nieto (2011, p. 135) and Lynn (1986).

o Following their feedback, four items per dimension were refined, and one item

from each variable was removed.

3. Piloting and adjustment

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

1937 Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences | Vol. 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

o The instrument was piloted with a group of 15 DJs and music producers,

consistent with the guidelines of Hair et al. (2010).

o Based on their feedback, adjustments were made regarding clarity, length, and

format; three items were revised, and overly technical language was simplified.

4. Final administration

o The survey was distributed online between July and August 2025 to 120

participants.

o The effective response rate reached 98%, yielding 118 valid questionnaires.

Internal consistency was assessed through the overall Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of

0.93, with the dimensions ranging from 0.85 to 0.92, which reflects a high level of reliability.

In the final phase, the measurement instrument was applied to a sample of 135 DJs and

music producers who currently act as directors of their own companies and as managers of the

businesses forming the unit of analysis. Following the recommendations of Lloret-Segura et al.

(2014), MacCallum et al. (1999), and Preacher & MacCallum (2003), the use of structural

equation modeling (SEM) was considered appropriate.

Qualitative component

Four focused interviews were conducted, which made it possible to construct a

Comparative Matrix of Dynamic Capabilities in DJs and Music Producers:

• Semi-structured interviews of 60–90 minutes in length were conducted, audio-recorded,

and transcribed verbatim.

RESULT

The outcomes of this study, in their positive aspect, are grounded in a thorough

examination of the data collected and analyzed following the methodology previously outlined.

By applying structural equation modeling, the proposed hypotheses were tested, uncovering

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

1938 Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences | Vol. 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

significant patterns, interrelationships, and effects among the variables under consideration.

This section provides a detailed account of the results, encompassing the construction of

predictive models, the assessment of model fit indices, and the estimation of essential

parameters. Together, these elements contribute to a complete and precise understanding of

the factors studied and their relevance within the explored context.

The contrast analysis aimed at evaluating the influence of the dependent variables —

Dynamic Absorptive Capacity, Dynamic Adaptive Capacity, Dynamic Learning Capacity,

Dynamic Innovation Capacity, and Dynamic Resilience Capacity— on the independent variable

(the Nature Type of these Capacities-Ontological) was performed using the SPSS and PLS

platforms, both recognized as appropriate technological tools for exploratory research.

Following Cohen (1998), the ƒ² index for the five variables demonstrated a strong association

with the coefficient of determination (R²), which reached a value of 81.91%. This outcome

highlights a substantial degree of dependence and significance among the variables under

examination.

Table 1

The Effects of Dependent Variables on the Independent Variable

Variables

Effects ƒ2

Total Effect

Dynamic Absorptive Capacity

0.335

Adequate or Relevant

Dynamic Adaptive Capacity

0.329

Adequate or Relevant

Dynamic Learning Capacity

0.323

Adequate or Relevant

Dynamic Innovation Capacity

0.332

Adequate or Relevant

Dynamic Resilience Capacity

0.310

Adequate or Relevant

The Nature Type of these Capacities

(Ontological)

0.315

Adequate or Relevant

Note: Based on proprietary measurements analyzed using SPSS and PLS (2025)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

1939 Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences | Vol. 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

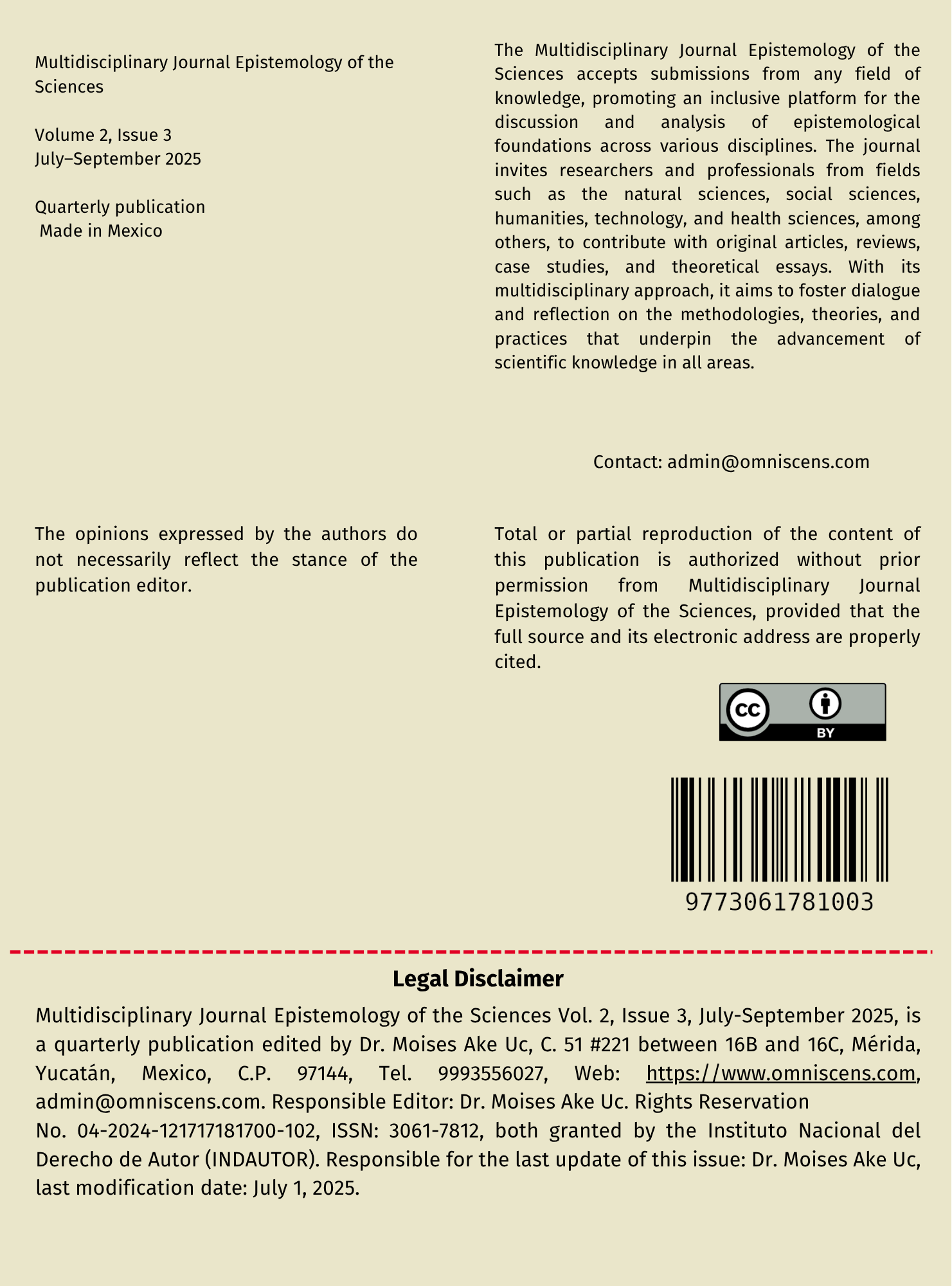

In the evaluation of the structural equation model (SEM) through the PLS method, Q²

values must be greater than zero to confirm the existence of an endogenous latent variable. As

illustrated in Figure 1, the Q² value obtained was 0.493, surpassing the required minimum

benchmark. This finding reinforces and validates the predictive capacity of the proposed model.

The results related to the eclectic, competence-based, and procedural natures were discarded.

Figure 1

Predictive model

Note: Prepared based on calculations in SPSS and PLS (2025)

The goodness-of-fit index (GOF) was applied to evaluate how well the model captures

and represents the empirical data. This measure ranges from 0 to 1 and is interpreted using

common thresholds: 0.10 reflects a weak fit, 0.25 a moderate fit, and 0.36 a strong fit. The

findings of the analysis revealed that the model is both parsimonious and aligned with the

observed data. The GOF value was derived by computing the geometric mean between the

average communality —also referred to as the Average Variance Extracted (AVE)— and the

mean of the R² values, thereby strengthening the evidence for the model’s overall validity.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

1940 Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences | Vol. 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

Table 2

Computation of the Goodness-of-Fit (GOF) Index

Constructs

AVE

R2

Dynamic Absorptive Capacity

0.671

Dynamic Adaptive Capacity

0.658

Dynamic Learning Capacity

0.633

Dynamic Innovation Capacity

0.648

Dynamic Resilience Capacity

0.647

The Nature Type of these Capacities

(Ontological)

0.659

0.7465

Average Values

3.809

0.7465

AVE * R2

0.4976

GOF = √AVE * R2

0.7056

Note: Based on proprietary measurements analyzed using SPSS and PLS (2025)

The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) —obtained from the discrepancy

between the observed correlations and the estimated covariance matrices— yielded a value of

0.057. Since this falls within the acceptable threshold (SRMR ≤ 0.09), the model demonstrates a

satisfactory fit. Furthermore, the Chi-square statistic reached 1914.023, while the Normed Fit

Index (NFI) was 0.799, both of which suggest that the measurement model can be regarded as

appropriate.

Table 3

Model estimators

Model estimators

SRMR

d_ULS

0.057

1.635

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

1941 Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences | Vol. 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

d_G1

d_G2

Chi-Square

NFI

0.927

0.779

1.914.023

0.799

Note: Based on proprietary measurements analyzed using SPSS and PLS (2025)

Finally, Table 4 presents the correlation coefficients among the latent variables, making it

possible to infer a strong association between the exogenous latent constructs and the

endogenous observed variables.

Table 4

Correlation of latent and observable variables

Note: Based on proprietary measurements analyzed using SPSS and PLS (2025)

The evaluation of the measurement model confirmed its suitability as a confirmatory

framework, showing that all proposed hypotheses reached statistical significance and were

therefore accepted. The results of this study demonstrate that the analyzed factors contributed

positively to shaping the concept of the Ontological Nature of these Capabilities in the Afrobeat

Music Sector (DJs and Music Producers) of Cartagena, thereby reinforcing its theoretical basis.

Variables

DAC

DAdC

DLC

DIC

DRC

NTC

Dynamic Absorptive Capacity

1.000

Dynamic Adaptive Capacity

0.264

1.000

Dynamic Learning Capacity

0.279

0.271

1.000

Dynamic Innovation Capacity

0.274

0.267

0.285

1.000

Dynamic Resilience Capacity

0.275

0.304

0.288

0.286

1.000

The Nature Type of these

Capacities (Ontological)

0.277

0.291

0.281

0.262

0.268

1.000

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

1942 Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences | Vol. 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

Nonetheless, the extent to which these findings can be generalized will rely on future studies

employing similar methodological designs.

Following the presentation of the quantitative results, the analysis of the qualitative

findings is introduced. For this purpose, semi-structured interviews were conducted with four

key figures from the DJ and music production scene in Cartagena (Colombia) and Miami (USA):

DJ Juandi García (J. D. Gamarra García, personal communication, August 9, 2025), DJ Jomi (J.

M. Mendoza Castro, personal communication, August 9, 2025), DJ Diego Jiménez (J. D.

Jiménez Jiménez, personal communication, August 11, 2025), and DJ Compund (A. C. Rincón

Baleta, personal communication, August 12, 2025). These expert voices provided valuable

insights into the Analysis of Dynamic Capabilities Applied to Music, which led to the

development of the following Comparative Matrix of Dynamic Capabilities in DJs and Music

Producers:

Table 5

Comparative Matrix of Dynamic Capabilities in DJs and Music Producers

DJ/Producer

Absorptive

Capacity

Adaptive

Capacity

Learning

Capacity

Innovative

Capacity

Resilience

Capacity

DJ Compund

(Andrés Camilo)

Incorporates

Afrobeat and

Dancehall

while

maintaining

his personal

style【26】

Uses TikTok

and live

sessions to

connect with

audiences

【26】

Corrects early

mistakes in

percussion and

identity【26】

Uses a

Nestum tin

can as

percussion【

26】

Transforms

breakups and

personal losses

into music【26】

DJ Jomi (José

Miguel)

Absorbs

African and

Jamaican

roots,

adapting them

to the coastal

Colombian

style【27】

Tests new

songs through

previews on

social media

【27】

Professionalizes

his production in

international

studios【27】

Creates Afro

house and

ballad fusion

with pianos

in Inolvidable

【27】

Overcomes

personal disputes

and remains

relevant【27】

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

1943 Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences | Vol. 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

DJ Juandi

García

Introduces

international

rhythms while

keeping his

coastal accent

【28】

Uses TikTok

trends and

choreographies

【28】

Improves vocal

control and

achieves cleaner

production

【28】

Borondo

album blends

acoustic

guitars with

Afrobeat

beats

【28】

Recovers from low

exposure periods

with strategic

relaunches

【28】

DJ Diego

Jiménez

Maintains

Afrobeat and

adapts it to

current

sounds

【29】

Relies on digital

marketing and

audience

closeness

【29】

Discipline and

consistency

refine his vocal

technique

【29】

Si Te Pillara

merges pop

and Afrobeat

【29】

Returns after

inactivity with a

fresh proposal

【29】

Note: Own elaboration (2025)

The comparative matrix demonstrates that the five dynamic capabilities—absorption,

adaptation, learning, innovation, and resilience—emerged consistently across the insights

provided by the four DJs and music producers when reflecting on Beéle’s Borondo album. Their

accounts reveal how external influences are absorbed and redefined in the artist’s sound, how

he adapts global trends to Caribbean contexts, and how his trajectory evidences a process of

continuous learning and professionalization. Likewise, Borondo illustrates Beéle’s capacity for

innovation, blending Afrobeat with acoustic and digital elements, and his resilience in

transforming personal and industry challenges into creative output. From these perspectives, it

can be inferred—within the inherent limitations of qualitative results—that the dynamic

capabilities analyzed are ontological in nature, as they are embedded not only in organizational

logics but also in the very identity, creativity, and cultural grounding of the artist himself.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study confirm the ontological nature of Dynamic Capabilities (DCs) in

the Afrobeat music sector, particularly within the trajectories of DJs and producers in Cartagena

de Indias (Colombia). The results obtained through structural equation modeling demonstrated

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

1944 Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences | Vol. 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

that absorptive, adaptive, learning, innovative, and resilience capacities are not only

competence-based or procedural (eclectic), but also operate as higher-order mechanisms

embedded in the artistic and organizational identity of the actors. This reinforces Teece’s (2007,

2018) claim that DCs constitute real generative mechanisms enabling firms to sense, seize, and

transform opportunities in turbulent environments, and expands this claim into the creative

industries, where artistic logics converge with managerial ones.

Theoretical contributions

First, the study provides empirical support for the eclectic and integrated view previously

advanced by Mendoza Betin (2018, 2019), while showing that only the ontological perspective

fully explains the observed dynamics in the case of Beéle’s Borondo album. Whereas

competence-based and procedural interpretations help describe routines and skills, they proved

insufficient to capture the depth of transformation identified in both quantitative and qualitative

data. The consistency across DJs’ testimonies suggests that DCs in the music sector are not

merely operational processes but essential elements of cultural and creative survival. In this

sense, the results extend the debate between Eisenhardt and Martin’s (2000) emphasis on

patterned routines and Teece’s focus on idiosyncratic orchestration, by demonstrating that in

creative industries, both aspects converge ontologically in the artist’s practice.

Second, the study enriches the literature on learning processes within DCs (Zollo &

Winter, 2002) by showing how rehearsal–feedback–revision cycles in music function as a

codification of artistic knowledge. Path dependence and path creation, highlighted by Helfat

(2009), also appear in the way DJs and producers transform previous trajectories into new

innovations, confirming the evolutionary and cumulative nature of these capabilities. The

integrative model tested here, with a goodness-of-fit index of 0.7056 and strong predictive

validity, empirically validates this ontological dimension, but with limitations.

Practical implications

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

1945 Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences | Vol. 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

For practitioners in the music industry, the findings suggest that sustainability of artistic

careers depends not only on technical skills or market positioning, but on the ability to enact

dynamic capabilities ontologically. For example, Beéle’s ability to hybridize Afrobeat with

acoustic and digital elements, or to transform personal and industry challenges into creative

outputs, exemplifies how resilience, innovation, and adaptation become central mechanisms of

career sustainability. DJs and producers may thus enhance their long-term relevance by

cultivating these capacities as core elements of their artistic identity.

Limitations and future research

Despite these contributions, the study has limitations. The sample was restricted to DJs

and producers in Cartagena, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, while

structural equation modeling provided strong evidence for the ontological nature of DCs,

longitudinal studies would allow a deeper exploration of how these capacities evolve across

different stages of artistic careers. Future research should expand the geographical scope to

other Latin American contexts and integrate additional variables such as digital platform

dynamics, collaboration networks, and audience communities, which may mediate or moderate

the effects of DCs on career sustainability.

CONCLUSION

Overall, the study demonstrates that in the Afrobeat music sector, DCs are best

understood as ontological mechanisms. They transcend competence-based and procedural

interpretations by embedding themselves in the cultural, organizational, and artistic essence of

DJs and producers. In doing so, they provide not only an explanation for competitive advantage

but also a lens to understand how artistic identities and practices sustain themselves in dynamic

and uncertain environments.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

1946 Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences | Vol. 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

Declaration of conflict of interest

The researcher declares that there is no conflict of interest related to this research.

Author contribution statement

Javier Alfonso Mendoza Betin: conceptualization, formal data analysis, investigation,

methodology, project administration, resources, software, supervision, validation, visualization,

writing – original draft, review and editing.

Statement on the use of Artificial Intelligence

The author declares that Artificial Intelligence was used as a support tool for this article,

and that this tool in no way replaced the intellectual task or process. The author expressly states

and acknowledges that this work is the result of their own intellectual effort and has not been

published on any electronic artificial intelligence platform.

REFERENCES

Adner, R., & Helfat, C. E. (2003). Corporate effects and dynamic managerial

capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 24(10), 1011–

1025. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.331

Ambrosini, V., & Bowman, C. (2009). What are dynamic capabilities and are they a useful

construct in strategic management? International Journal of Management Reviews,

11(1), 29–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2008.00251.x

Barreto, I. (2010). Dynamic capabilities: A review of past research and an agenda for the

future. Journal of Management, 36(1), 256–

280. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309350776

Beéle. (2025). Borondo [Álbum]. Hear This Music LLC bajo licencia exclusiva de 5020 Records.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence

Erlbaum Associates.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

1947 Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences | Vol. 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

Di Stefano, G., Peteraf, M., & Verona, G. (2010). Dynamic capabilities deconstructed. Industrial

and Corporate Change, 19(4), 1187–1204. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtq027

Drnevich, P. L., & Kriauciunas, A. P. (2011). Clarifying the RBV and DCV. Strategic

Management Journal, 32(3), 254–279. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.878

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Martin, J. A. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strategic

Management Journal, 21(10–11), 1105–1121. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-

0266(200010/11)21:10/11<1105::AID-SMJ133>3.0.CO;2-E

Fainshmidt, S., Pezeshkan, A., Frazier, M. L., Nair, A., & Markowski, E. (2016). Dynamic

capabilities and organizational performance: A meta-analytic evaluation and

extension. Journal of Management Studies, 53(8), 1348–

1380. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12213

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2010). Multivariate data

analysis (7th ed.). Prentice Hall.

Helfat, C. E. (2009). Understanding dynamic capabilities: Progress along a developmental

path. Strategic Organization, 7(1), 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127008100133

Helfat, C. E., & Peteraf, M. A. (2003). The dynamic resource-based view: Capability

lifecycles. Strategic Management Journal, 24(10), 997–

1010. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.332

Helfat, C. E., & Peteraf, M. A. (2015). Managerial cognitive capabilities and the

microfoundations of dynamic capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 36(6), 831–

850. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2247

Helfat, C. E., & Winter, S. G. (2011). Untangling dynamic and operational capabilities. Strategic

Management Journal, 32(3), 1243–1250. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.955

Hernández-Nieto, R. A. (2011). Contribuciones al análisis de la validez de contenido: Una

revisión conceptual y metodológica. Universidad de Los Andes.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

1948 Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences | Vol. 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

Laaksonen, O., & Peltoniemi, M. (2018). The essence of dynamic capabilities and their

measurement. International Journal of Management Reviews, 20(2), 184–

205. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12122

Lloret-Segura, S., Ferreres-Traver, A., Hernández-Baeza, A., & Tomás-Marco, I. (2014). El

análisis factorial exploratorio de los ítems: una guía práctica, revisada y

actualizada. Anales de Psicología, 30(3), 1151–

1169. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.30.3.199361

Lynn, M. R. (1986). Determination and quantification of content validity. Nursing Research,

35(6), 382–385. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-198611000-00017

MacCallum, R. C., Widaman, K. F., Zhang, S., & Hong, S. (1999). Sample size in factor

analysis. Psychological Methods, 4(1), 84–99. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.4.1.84

Maturana, H. R., & Varela, F. J. (1980). Autopoiesis and cognition: The realization of the living.

D. Reidel. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-8947-4

Maturana, H. R., & Varela, F. J. (1987). The tree of knowledge: The biological roots of human

understanding. Shambhala Publications.

Mendoza Betin, J. A. (2018). Capacidades dinámicas: Un análisis empírico de su

naturaleza. MLS Educational Research, 2(2), 193–

210. https://doi.org/10.29314/mlser.v2i2.80

Mendoza Betin, J. A. (2019). Capacidades dinámicas y rentabilidad financiera: Análisis desde

una perspectiva ecléctica en empresas de saneamiento básico de Cartagena (Tesis

doctoral, Universidad Internacional Iberoamericana, México).

Mendoza-Betin, J. A. (2021). Resiliencia empresarial: Análisis empírico de Aguas de Cartagena

S.A. E.S.P. Revista Científica Anfibios, 4(1), 11–

26. https://doi.org/10.37979/afb.2021v4n1.80

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

1949 Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences | Vol. 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

Mendoza Betin, J. A. (2025). Beéle: Genialidad y coletera. KDP

Amazon. https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0FMZHFWZL

Mendoza Betin, J. A. (2025). Beéle y las capacidades dinámicas en la industria musical

contemporánea. Revista Multidisciplinar Epistemología de las Ciencias, 2(3), 1396–

1411. https://doi.org/10.71112/vqv0ww84

Mikalef, P., Krogstie, J., Pappas, I. O., & Pavlou, P. A. (2020). Big data analytics capabilities

and firm performance. Information & Management, 57(2),

103208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2019.103208

Mintzberg, H. (1994). The rise and fall of strategic planning. Free Press.

Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995). The knowledge-creating company: How Japanese

companies create the dynamics of innovation. Oxford University Press.

Pavlou, P. A., & El Sawy, O. A. (2011). Understanding the elusive black box of dynamic

capabilities. MIS Quarterly, 35(1), 137–169. https://doi.org/10.2307/23043489

Peteraf, M. A., Di Stefano, G., & Verona, G. (2013). The elephant in the room of dynamic

capabilities: Bringing two diverging conversations together. Strategic Management

Journal, 34(12), 1389–1410. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2078

Piening, E. P. (2013). Dynamic capabilities in public organizations. Public Management Review,

15(2), 209–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.822535

Preacher, K. J., & MacCallum, R. C. (2003). Repairing Tom Swift’s electric factor analysis

machine. Understanding Statistics, 2(1), 13–

32. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328031US0201_02

Protogerou, A., Caloghirou, Y., & Lioukas, S. (2012). Dynamic capabilities and their indirect

impact on firm performance. Industrial and Corporate Change, 21(3), 615–

647. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dts008

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

1950 Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences | Vol. 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

Schilke, O. (2014). On the contingent value of dynamic capabilities for competitive

advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 35(2), 179–

203. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2099

Schilke, O., Hu, S., & Helfat, C. E. (2018). Quo vadis, dynamic capabilities? Academy of

Management Annals, 12(1), 390–439. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2016.0014

Schreyögg, G., & Kliesch-Eberl, M. (2007). How dynamic can organizational capabilities

be? Organization Studies, 28(6), 913–933. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840607078110

Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of

(sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28(13), 1319–

1350. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.640

Teece, D. J. (2014). A dynamic capabilities-based entrepreneurial theory of the MNE. Journal of

International Business Studies, 45(1), 8–37. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2013.54

Teece, D. J. (2018). Business models and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Planning, 51(1),

40–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2017.06.007

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic

management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–

533. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199708)18:7<509::AID-SMJ882>3.0.CO;2-

Z

Verona, G., & Ravasi, D. (2003). Unbundling dynamic capabilities: An exploratory

study. Organization Science, 14(4), 350–

363. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.14.4.537.17484

Wang, C. L., & Ahmed, P. K. (2007). Dynamic capabilities: A review and research

agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 9(1), 31–

51. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2007.00213.x

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71112/h4ybam13

1951 Multidisciplinary Journal Epistemology of the Sciences | Vol. 2, Issue 3, 2025, July–September

Wilden, R., Gudergan, S. P., Nielsen, B. B., & Lings, I. (2013). Dynamic capabilities and

performance: Strategy, structure and environment. Long Range Planning, 46(1–2), 72–

96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2012.12.001

Winter, S. G. (2003). Understanding dynamic capabilities. Strategic Management Journal,

24(10), 991–995. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.318

Zahra, S. A., Sapienza, H. J., & Davidsson, P. (2006). Entrepreneurship and dynamic

capabilities. Journal of Management Studies, 43(4), 917–

955. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00616.x

Zollo, M., & Winter, S. G. (2002). Deliberate learning and the evolution of dynamic

capabilities. Organization Science, 13(3), 339–

351. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.13.3.339.2780